This post is based on a talk by Eskil Andréen, CTO of Wrapp. Some parts are directly taken from his presentation, while other are my personal view on the topic. If you like any of what you read thank Eskil if you don’t blame me :)

What is Wrapp

Wrapp was founded around 4 years ago and the first version of the product was an application to send digital gift cards to your Facebook friends. A bit more than a year ago the company pivoted and the new product is a loyalty platform that integrates with your credit/debit card and automatically gives discounts based on your purchase behavior.

When it was decided to pivot and close the old service we took the decision of getting rid of all our backend infrastructure and start from scratch with a new architecture based on microservices. The requirements for the new architecture were scalability, availability and ease to introduce changes.

We are currently 14 people in the tech team and all our infrastructure runs on Amazon Web Services (AWS).

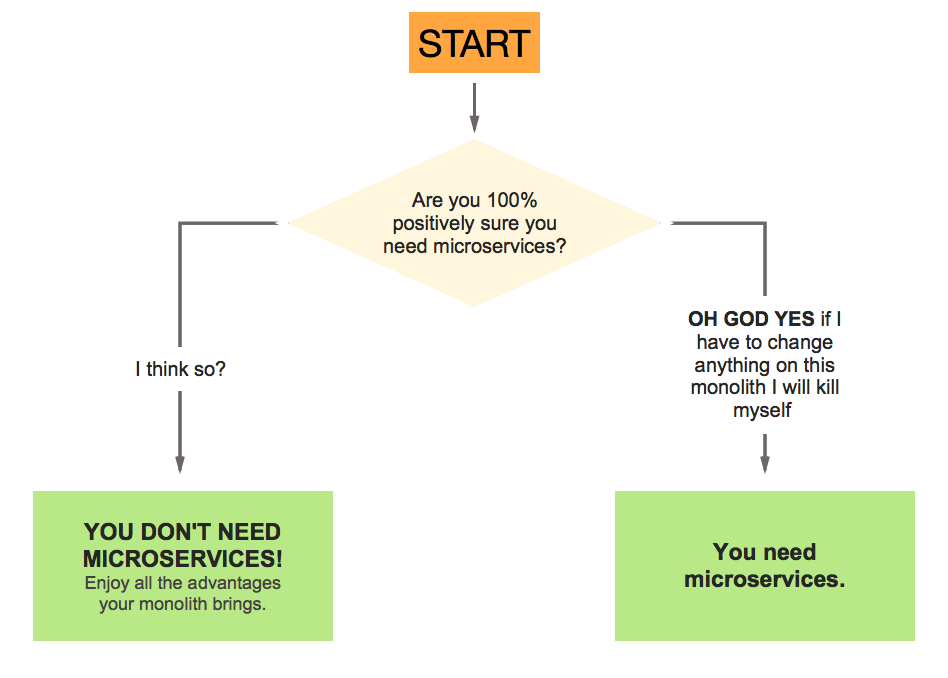

Why microservices at Wrapp

At the time when the pivot was started our backend consisted of a few monolithic applications written in Python that after three years of fast paced development were messy and full of technical debt.

To make things worse there were a lot of shared dependencies between the applications and this required a complex infrastructure. We also had a tone of tests and that made introducing changes to the existing code harder.

We hoped that microservices would help to prevent those issues. With microservices each component is small and simple, which means that it is more feasible to keep the code well organized and less tests are required.

We also wanted to make work more rewarding by allowing developers to design their components as they wish, with the tools they want (language, libraries, frameworks…) and because smaller units of work are more satisfying to complete. Finally, encouraging collective ownership by involving everyone in the design and implementation of complete parts of the system.

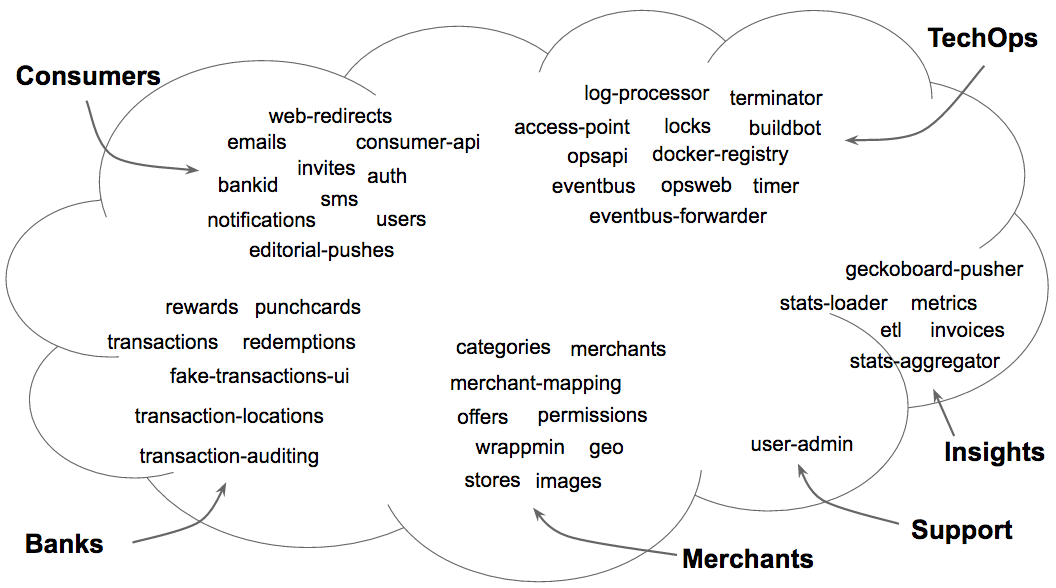

How does Wrapp look now

One year after starting the complete rewrite of our backend we have launched a new product and doubled the size of the tech team. Our backend is formed by around 50 services, each one run as Docker container, mainly written in Python and Go; Everything that is important for our product is a service. In this word cloud you can see most of the services that conform Wrapp’s backend:

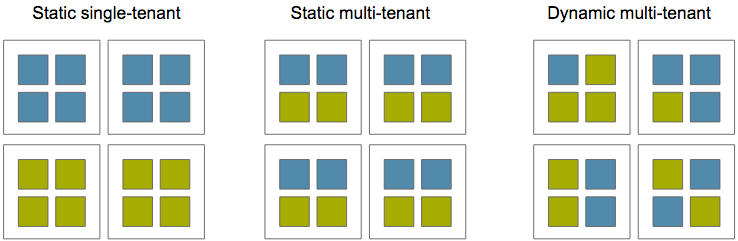

Tenancy or where to run each service

We started with the simplest approach, single-tenancy: Each server runs a single type of service. The main benefit of this approach is its simplicity, the problem though is that it is wasteful as many services are idling most of the time or are very small and don’t use all the resources of the machine where they run.

To solve that we evolved to static multi-tenancy: Each server runs a predefined set of services. This partially solves the issues of single-tenancy, but forces you to manually decide how to group services.

Finally we are using dynamic multi-tenancy: Services are dynamically assigned to hosts without any per-host static configuration. We use Amazon ECS to manage the placement of our services.

Service discovery

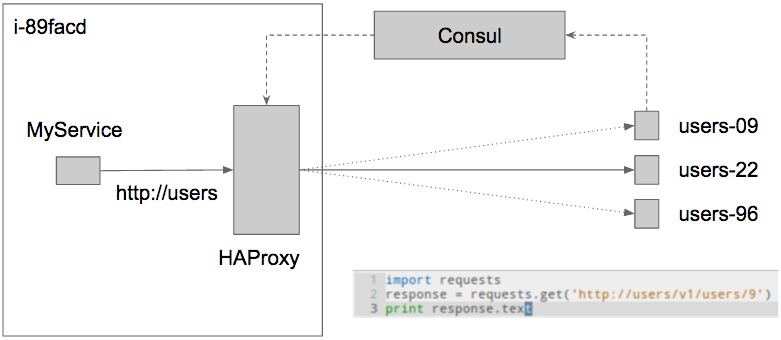

After a few iterations we have a solution that transparently handles addition and deletion of services and is based on DNS, Consul, Registrator and HAProxy.

Our solution requires us to assign a different private IP address from a predefined IP range to every service. For convenience we map the service name to their private IP address using DNS. Then Registrator, Consul Agent and HAProxy run in each server of the cluster:

- Registrator inspects Docker containers as they come online/offline and informs the local Consul Agent of the services that they run.

- Consul Agent periodically registers the services that are running in the machine to the Consul Catalog and refreshes the configuration of the local HAProxy to include all the services listed in the Catalog via consul-template.

- The range of private IP addresses that are mapped to the different services are configured as aliases for the local loopback device. Haproxy binds to each of these IP addresses and load balances the requests among the available instances of the respective service.

To better understand this mechanism, lets use an example; Suppose we are adding a new service into our cluster, the users service, this is what happens:

- We assign the IP address

192.186.10.1to the users service and add the DNS nameusers.internal.ourdomainmapping to that IP. - The new service is deployed, and it starts running in a subset of our servers.

- Registrator running in those servers detects a new Docker container running the users service and informs the Consul Agent. Consul Agent will register it to the Consul Catalog.

- The Consul Agent running in each server eventually gets the new list of services from the Consul Catalog and updates the local HAProxy configuration adding a new backend to serve requests to the IP address assigned to the users service

192.186.10.1. - Finally, when when a request is issued to

users.internal.ourdomainthe DNS name is resolved to192.186.10.1and the local HAProxy receives the request and forwards it to one of the instances of the users service.

By default the services are only accessible from within our network. For services that need to be accessible from the internet we have a service connected to a public load balancer that takes care of receiving requests and forward them to the specified internal service.

Inter-service Communication

Each service exposes a REST API and inter-service communication is done over HTTP with JSON payloads. Communication can be synchronous HTTP requests or it can be done using the eventbus.

The eventbus is in itself a microservice that offers publish/subscribe functionality. It is built on top of Amazon SQS and SNS. It guarantees at least once delivery and automatically retries failed requests. We use this way of communication for all the tasks that don’t require an immediate response.

Given the amount of services and requests involved in performing any complex task, it is not strange that one of them fails. For this reason it is a good practice to have retrials on requests. This means that requests must be idempotent, issuing the same request multiple times should always produce the same result. From our experience, having retrials and idempotent requests really helps in dealing with the complexity that aries from working in a distributed system.

Monitoring

It is a complex system with lots of moving parts, so there are many things to monitor and we use a few different strategies:

- Monitor logs for warnings, errors and deviations.

- Monitor Network traffic: number of requests, latency, percentage or errors.

- Define and monitor KPIs for each service important service.

You can check out this blog post Monitoring microservices with haproxy and riemann to know more about our monitoring tools.

Conclusion

After one year working with microservices they have brought a lot of good things to our organization and have been overall a great choice, confirming most of our initial expectations. We have a relatively big and complex system, composed by many small and simple services. This means that it is simple to understand, extend and even replace individual components of our backend, giving us great flexibility. Furthermore we feel that microservices have a great positive impact in developer satisfaction.

We also face a few issues from using microservices. First of all it was a big upfront time investment to develop the required infrastructure to support microservices: deployment, service discovery, monitoring…

Secondly, distributed systems are hard and with microservices we face all the issues that come with them regarding consistency, atomicity and concurrency. It is also hard to cleanly split complex functionalities between multiple services and model the interactions between them while keeping the involved services decoupled.

Finally there is an important overhead in implementing and maintaining HTTP interfaces and clients for each service and we face higher latency due to multiple http hops. Any common task performed by the clients of our API requires tens of HTTP requests between different services.

A special mention is also reserved for testing; Our approach is having a strict contract for the interface of each component and focus our testing efforts in internal service tests that make sure that the contract is satisfied. But it is hard to be sure that interactions between services will work as expected when they are put together and we haven’t found a good way of performing automatic integration tests.

For all these reasons is probably not a good idea to use microservices for small projects or those that have well defined and non-changing requirements, as then the benefits of microservices are less obvious.